Impetus for Action

Yes, it takes a village to raise a child. Sometimes it also takes a performance whisperer.

A few years ago, David Hunter, a tough-love consultant, spoke on a panel in Boston alongside Daniela Barone Soares, then the CEO of Impetus Trust, a UK-based, non-endowed foundation. Soares was blown away by Hunter’s unique blend of passion and rigor. She invited him to London to help shake up her team.

The timing was perfect. Impetus Trust was completing a merger with The Private Equity Foundation to form Impetus-PEF, dedicated to improving the lives of disadvantaged youth in the UK. “As an organization, we had always been worried we weren’t doing enough,” recalls Jenny North, Impetus-PEF’s director of policy and strategy. “The merger gave us a chance to take a hard look.”

North’s colleague Chiku Bernardi, a Brit born in India and one of the firm’s investment directors, explains, “We had been operating under the assumption that the charity leaders knew their product, and we weren’t supposed to look into it…. We didn’t have the confidence to ask tougher, more analytical questions about effectiveness.”

[Impetus-PEF] is now the funder that has the best-worked-out and -implemented approach to social investing, bar none.

—David Hunter,

Managing Partner, Hunter Consulting

After Hunter’s workshop and three years of implementing the blueprint that emerged, the organization and its new CEO, Andy Ratcliffe, are on a completely different path. Hunter, not one for doling out compliments, says that Impetus-PEF “is now the funder that has the best-worked-out and -implemented approach to social investing, bar none.”

In this profile, we’ll dive into Impetus-PEF’s model to understand the financial and intellectual resources it brings to bear for helping organizations become higher performers. We’ll hear from grantees to gain their perspective on the benefits of and pain points in Impetus-PEF’s approach. We’ll examine how Impetus-PEF is tracking its own outcomes, not just supporting grantees to do so. And we’ll learn from mistakes that Impetus-PEF has made during this journey.

We hope you’ll come away from this profile with an understanding of how and why one funder has boldly adopted a relentless focus on performance. We aim to give you food for thought and impetus for action.

Born of Frustration

Impetus Trust was the brainchild of Stephen Dawson, a British investor who led London-based ECI Partners, and Nat Sloane, an American-born entrepreneur, investor, and management consultant who has spent most of his career in the UK. Except for a just-the-facts-ma’am bio of Sloane, who continues to serve on the board of Impetus-PEF, you’ll find almost nothing about them on the Impetus-PEF website. Dawson and Sloane have taken great pains to avoid fanfare and limelight. (That effort was undermined by Queen Elizabeth herself, when she named Dawson an Officer of the British Empire and Sloane a Commander of the British Empire for their philanthropic work.) “Stephen is the most humble, retiring guy I’ve ever met,” says Bernardi. “Both of them would rather die in a ditch than read ‘founder stories’ about themselves.”

Dawson and Sloane became not only Impetus Trust’s key funders; they got deeply and personally involved in every philanthropic investment they made. According to North, “They did a lot of the work themselves. They had both had years of dissatisfaction with their philanthropic giving. They wanted to achieve more impact.”

Dawson and Sloane were particularly frustrated by the lack of scale in the social sector. Both men had significant professional experience helping companies grow and expand. Their mindset was, in North’s words, “If something’s good, it should scale.” And yet the funding system in the social sector practically ensured that good organizations would stagger along at modest scale. In the world they came from, investors deploy capital over the long term to build great institutions. In the social sector, charities are caught in a starvation cycle, living hand-to-mouth on small, short-term project grants.

Meanwhile, another group of private equity leaders in London were experiencing the same frustrations. These leaders, including KKR’s Johannes Huth, also wanted to deploy their skills, not just their checkbooks, to help charities achieve more. The Private Equity Foundation was born. This group saw the value of philanthropic focus for “moving the needle” on big problems. They chose to concentrate all their resources on the issue of youth unemployment. They built a portfolio of the best organizations tackling this problem from all angles.

Huth, who now serves as the chair of Impetus-PEF, says that he and his colleagues felt there was a great deal that funders and charity leaders could learn from the other “so that charities could operate more effectively, and we investment professionals could learn how and where to put our funds to work so it would have the greatest benefit.”

Good Intentions Are Not Good Enough

After the merger of the two organizations, Impetus-PEF’s leaders came to see that they had been putting the cart before the horse–scale in front of impact. “We learned that [our partners] needed to be much more confident on the impact side before scaling,” says Ratcliffe.

One of the big things we’ve seen from these trials is that even with the best of intentions, a lot of things don’t work.

—Andy Ratcliffe,

CEO, Impetus-PEF

Since Ratcliffe became CEO in 2016, he has been admonishing his staff and board to “beware the 75 percent success rate.” “Every charity has a 75 percent success rate,” he says. “That’s sort of a joke, sort of true. It’s the ‘keep the funder happy’ number.” Impetus-PEF now digs much deeper into the numbers. “Of that 75 percent, who got jobs? How many kept the job? For how long? Were they the right people? And by the way, if you helped 75 percent get a job, how many people dropped out of the program and are not factored into your 75 percent?”

Impetus-PEF credits Hunter with helping them see the need for an “impact first, then scale” mentality. When Hunter came to London, he challenged everyone in the room, including powerful board members not used to being questioned about their philanthropic efforts. Among other things, he pushed them to acknowledge that many of their grantees needed to build a stronger evidence base before they could know what was working for the disadvantaged young people they served.

In the process, Hunter inspired Impetus-PEF to raise the bar. “Many of our charities had been achieving some outcomes for some of the people they served. We now aspire to see them move on that journey toward great outcomes for all they serve–and to make sure they’re focusing their efforts on those who really need their support,” says Bernardi.

“Up until point where they met with David Hunter … the conversation with our investment director was all about scaling up,” recalls Jo Rice, the managing director of Resurgo, an Impetus-PEF grantee that helps disconnected young people find their way into jobs. “They were humble enough to say, ‘We’re having a change of heart.’”

Ratcliffe fully acknowledges that he and the team are far from having all the answers on impact. “We’re learning all the time … and it’s been painful at times,” he says.

Some of Impetus-PEF’s deepest–and most painful–learning about impact has come through the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), which Impetus-PEF helped create with The Sutton Trust and the UK Department for Education. With the help of rigorous external evaluators, EEF has been testing different approaches to closing the educational-attainment gap in the UK. “One of the big things we’ve seen from these trials is that even with the best of intentions, a lot of things don’t work,” says Ratcliffe. “It’s a stark message that if you want to get the best out of your philanthropic dollars, you have to invest in learning whether it works and whether it can sustain growth–before going hard on scale.”

Investing in Team

Impetus-PEF has learned that being serious about impact means investing serious money–not only in its grants (more than £4 million per year) but also in its own team. “You can’t create big change on spare change,” in the words of one nonprofit leader.

Impetus-PEF has 35 staff members, 14 of whom are on the team that selects grantees and supports their journey to higher performance. The personnel costs for this investment team represent about 20 to 30 percent of the amount Impetus-PEF gives out each year in grants.

The team is diverse in terms of race, ethnicity, culture, and gender. Team members have big brains and big hearts. Each also brings 15-20 years of hands-on experience helping for-profit, nonprofit, or public-sector organizations operate more effectively.

Ratcliffe, who most recently served as deputy chief executive of a global anti-poverty charity, has structured the team to give each member the time to work in close partnership with grantees. Each investment director manages just two or three grants at a time, far fewer than the typical foundation officer.

This organizational model is particularly noteworthy because Impetus-PEF is not an endowed foundation with a lot of room, and treasure, to experiment. It must raise its operating budget every year from individuals, foundations, and corporations. “We wish we had a big endowment. But we have it easier than many of our grantees, because have a longstanding relationship with the private equity industry,” North says.

Delivering the ‘Driving Impact’ Model

Impetus-PEF’s focus on impact begins with the grantee-selection process. Since the merger, the investment team has screened more than 2,000 charities, spoken with the leaders of hundreds, and invested in only 18 of them.

The investment team looks for grantees that fit its programmatic criteria: helping disadvantaged young people in the UK achieve in education and/or employment. That’s the easy part. The hard part is identifying those with the greatest potential to be high-performance organizations that deliver meaningful, measurable, and financially sustainable results for the young people who need them.

Finding these special organizations is both an art and a science. And it can take a long time. “The due diligence took almost a year,” says Rice. “They talked to every single member of our staff.”

Once Impetus-PEF selects a partner, the work gets more intensive. Impetus-PEF provides highly engaged support to the grantee CEO and senior management team. Where Bernardi and the other investment directors once felt unable to ask tough questions about the delivery model, they now dive deep, in a spirit of “empathetic challenge.”

Partnerships generally begin with investment directors leading multi-day Driving Impact workshops, a gentler but still rigorous version of the Hunter sessions that sparked profound introspection and change at Impetus-PEF. In one session Bernardi facilitated, she created a space for frontline staff to share hard truths with management. One of the hardest: The organization was inadvertently “creaming”–serving many people who didn’t have significant needs and, in the process, artificially inflating its outcome data. “Management was shocked and pained,” North reports. “But that led to brave decisions. They cut their caseloads in half, despite the cost implications. They knew that was necessary to get good outcomes with the people who really needed their help.”

Investment directors work hard to become a close ally and critical friend of the charity CEO. They spend more than 200 hours a year engaging with the organization–attending board meetings, coaching executives on change management, helping to build the organization’s leadership capacity, and helping to guide evaluation planning. “I’m really confident that to help transform their impact you need a deep and trusted relationship,” says Ratcliffe. “You need to see problems … not from outsider’s perspective. You need to be a trusted insider.”

Investment directors also play the role of matchmaker. They tap their pro bono network of 400 individuals from top UK management consulting, legal, accounting, and communications firms to find the best fit for projects that charity CEOs determine they need to undertake as part of their drive for higher performance.

Most of the pro bono consultants provide high value for grantees, but not all. When looking for a consultant for a particular project, “we’re looking for the right combination of brain power and expertise and humility,” says Ratcliffe. “It’s quite a rare thing to find a hotshot at the top of [his or her] industry who has the humility to understand that not everything they know will apply [in the social sector]. We’ve learned a lot about what we’re looking for. But we won’t always get it right to avoid proper car crashes.”

Rice averted one crash by rejecting the first consultant Impetus-PEF recommended. “He really didn’t listen,” she says. “He arrived with a suite of pre-determined ideas … that I knew instinctively were futile…. Impetus-PEF honored our view. And that set the tone for our relationship very well.”

Investment directors’ support spans the length of the Impetus-PEF investment, which can run for up to 10 years. When genuine trust develops, the relationship can be transformative. Investment Director Sebastien Ergas has worked closely with the CEO of The Access Project, a tutoring organization focused on getting students from disadvantaged areas to attend top universities. Early in the relationship, he found constructive ways to push CEO Andrew Berwick and colleagues to clarify their definition of success. “Right below the surface, there were some important differences of opinion within the organization on what they existed to do,” says Ergas. “When there’s ambiguity around what success looks like, it’s really hard to manage to outcomes.”

Our model works if there is a courageous leader who is willing to be challenged and let go of certain assumptions.

—Sebastien Ergas,

Investment Director, Impetus-PEF

Through their work with Ergas, Berwick and his board came to see that the organization’s outcomes weren’t strong enough. Because they were partnering with entire schools in disadvantaged areas rather than focusing on just the students in those schools who needed support, only half of The Access Project’s resources were going to truly disadvantaged students. The Access Project also came to see that to be effective, they needed to spend more time tutoring students. And the organization acknowledged that only one-third of the students they tutored actually ended up at highly selective universities, the organization’s top outcome.

“We did our part in asking new questions,” Ergas says. “But the success of our work ultimately hinges on leadership of the organization, especially the CEO. Our model works if there is a courageous leader who is willing to be challenged and let go of certain assumptions. The Access Project is great case study in a leader playing that role.”

In the three years since Ergas began working with The Access Project, the organization’s outcomes have dramatically improved. Today, 90 percent of all students served are truly disadvantaged (up from 50 percent). The “dosage” of tutoring has increased by 50 percent. More than 50 percent of students are now placing at highly selective universities (up from around a third). And Ergas helped Berwick achieve these improvements without significant change in delivery costs. “Their tutoring is delivered by volunteers, and the organization didn’t have to add coordinators or change case loads substantially,” he reports.

To learn more about Impetus-PEF’s approach, check out “Driving Impact,” which does a brilliant job of documenting exactly how Impetus-PEF helps its grantees clarify their mission and target population, strengthen their program design, monitor their progress, and achieve greater impact. You’ll love the concreteness of the section in which Impetus-PEF shares before-and-after illustrations of how its grantees evolved during the course of working with Impetus-PEF’s investment directors.

A Grantee’s Perspective

Of course, all of this hands-on help can take a toll on grantees. That’s why we reached out to Resurgo’s Rice to get her perspective on whether this rigor is a true value-add or just a lot of hoop-jumping. In her view, it’s not only worth the effort; it’s indispensable.

“Our experience has been so outstanding,” she says. “They are by far the most invested funder of ours, not just in terms of money but in terms of all forms of support…. It’s fair to say that money was the reason we embarked on the relationship, but it quickly became clear that the real value was …. in the relationship with our investment director…. I’m not afraid of her seeing our data. She knows everything. I trust her. And she trusts us to deploy their resources where we see fit.”

Our experience has been so outstanding. They are by far the most invested funder of ours, not just in terms of money but in terms of all forms of support.

—Jo Rice

Managing Director, Resurgo

Rice says that she and her investment director, Bernardi, have difficult conversations without negative consequences. “She can tell me ‘You didn’t bring your A game to that meeting,’ and I can tell her that I think Impetus was out of balance in placing too much focus on impact without paying equal attention to sustainability. We can have those robust conversations without me fearing that they will pull the plug.”

Rice shares a story that illustrates the reciprocity of the learning relationship between Resurgo and Impetus-PEF. Impetus-PEF’s CFO Richard Lackmann decided of his own accord to take Resurgo’s five-day corporate leadership training. He was impressed by the training, especially the way Resurgo teaches and promotes “emotional intelligence.” Lackmann asked Rice if she and her colleagues would provide similar training for every member of Impetus-PEF’s team, from the CEO to the newest apprentice.

Rice shares a story that illustrates the reciprocity of the learning relationship between Resurgo and Impetus-PEF. Impetus-PEF’s CFO Richard Lackmann decided of his own accord to take Resurgo’s five-day corporate leadership training. He was impressed by the training, especially the way Resurgo teaches and promotes “emotional intelligence.” Lackmann asked Rice if she and her colleagues would provide similar training for every member of Impetus-PEF’s team, from the CEO to the newest apprentice.

Rice believes that all of this trust has translated directly into improved results for Resurgo–and she has data to back up that belief. Rice shared employment, education, and training outcome data culled from the organization’s performance-management system. Since Resurgo implemented a series of staff and programmatic changes prompted by its work with Impetus-PEF, three-month intended outcomes in its main program have increased by a full 20 percentage points.

Taking the Same Medicine

Impetus-PEF has committed to helping all of its grantees develop performance-management systems. Far more unusual is Impetus-PEF’s decision to develop its own robust performance-management system, using the well-known Salesforce platform. “We use performance management for our own management,” comments Elisabeth Paulson, a transplanted American who oversees the overall direction of Impetus-PEF’s portfolio. “As a team, we look at how the charities are progressing and how we can take advantage of the different strengths that each member of the investment team brings to the table.”

Ratcliffe is driving his organization to develop goals as clear as those it encourages its grantees to develop. “I’ve asked the team to focus more since I’ve come into this role. We’ve had a great portfolio for a few years, and these organizations are … growing and delivering better service to young people. I’ve asked our team to [get a clearer understanding of] what all this will add up to five years from now. How many young people are passing their exams, how many more at top universities, how many more in employment?”

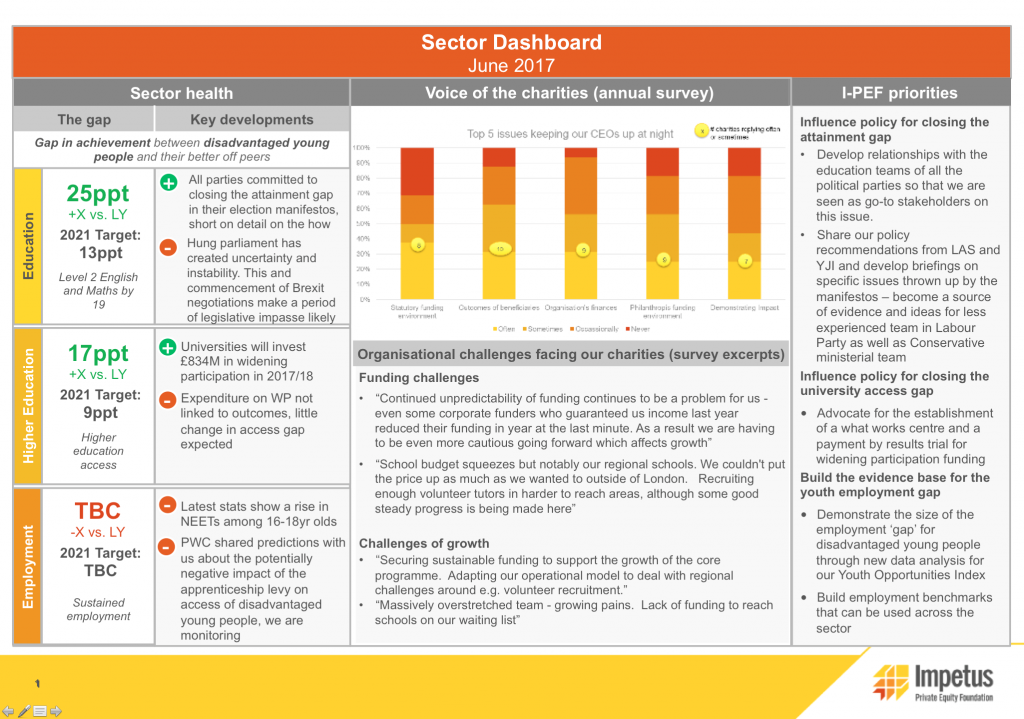

Impetus-PEF has long acknowledged that it’s only a small part of a larger education and employment systems. But Ratcliffe feels it’s essential for Impetus-PEF to identify sector-wide goals and then determine what role Impetus-PEF must play to help the sector achieve those goals. Here’s what those sector-wide goals look like for education:

- Primary and Secondary: Halve the gap between disadvantaged young people and their better-off peers by 2021. (The gap is currently 25 percentage points for 16-year-olds.)

- Higher Education: Halve the gap between disadvantaged young people and their peers by 2021 in access to university. (The gap is currently 17 percentage points.)

For employment, there is less available data on how young people from disadvantaged backgrounds fare in the labor market compared to their better-off peers. Impetus-PEF has commissioned research into linked, longitudinal datasets that should reveal the answer next year. This will inform the team as they set goals to reduce the disparity. Just as important, this research will inform policymakers and funders about the true extent of the employment problem and galvanize public and private actors to help Impetus-PEF solve it.

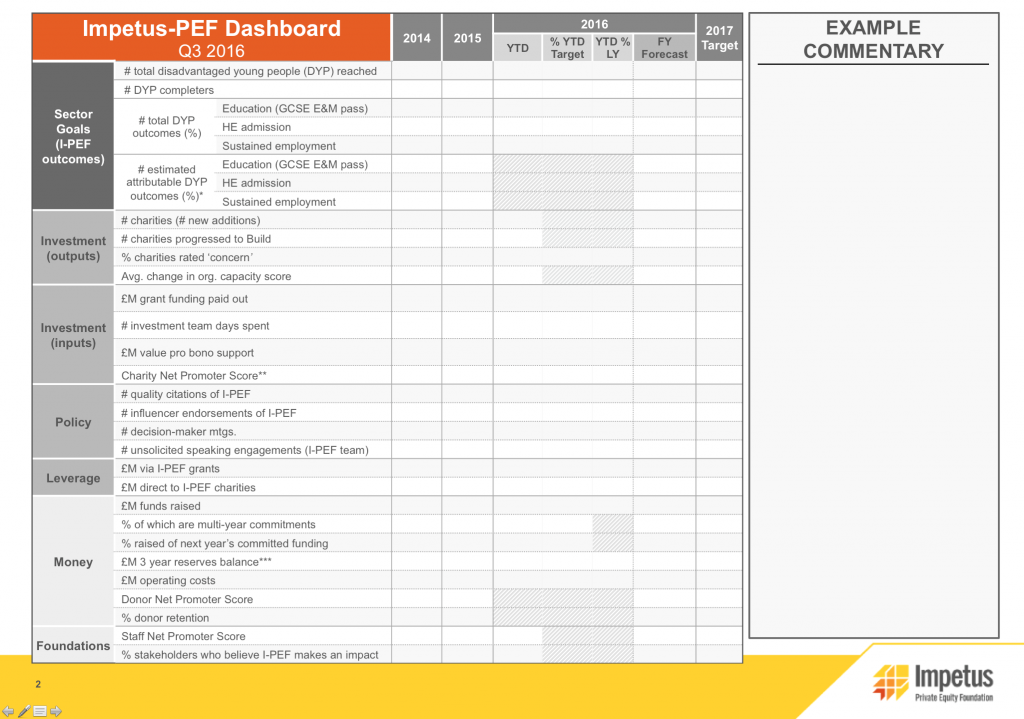

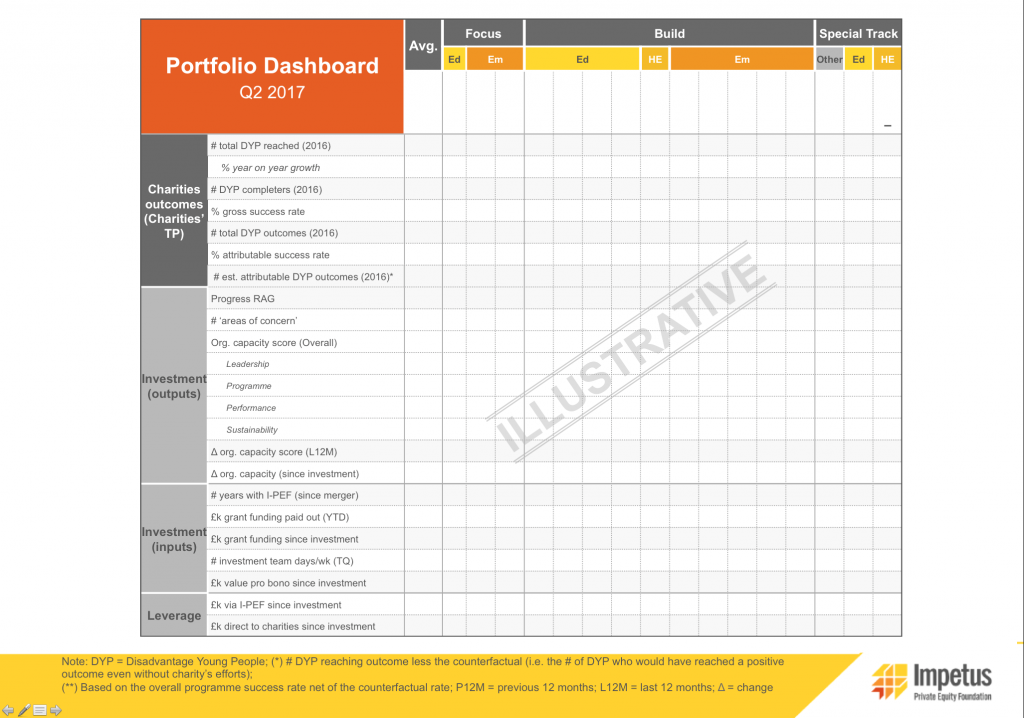

To monitor progress and create the basis for learning and improvement, Impetus-PEF is developing three new dashboards that draw data from its performance-management system

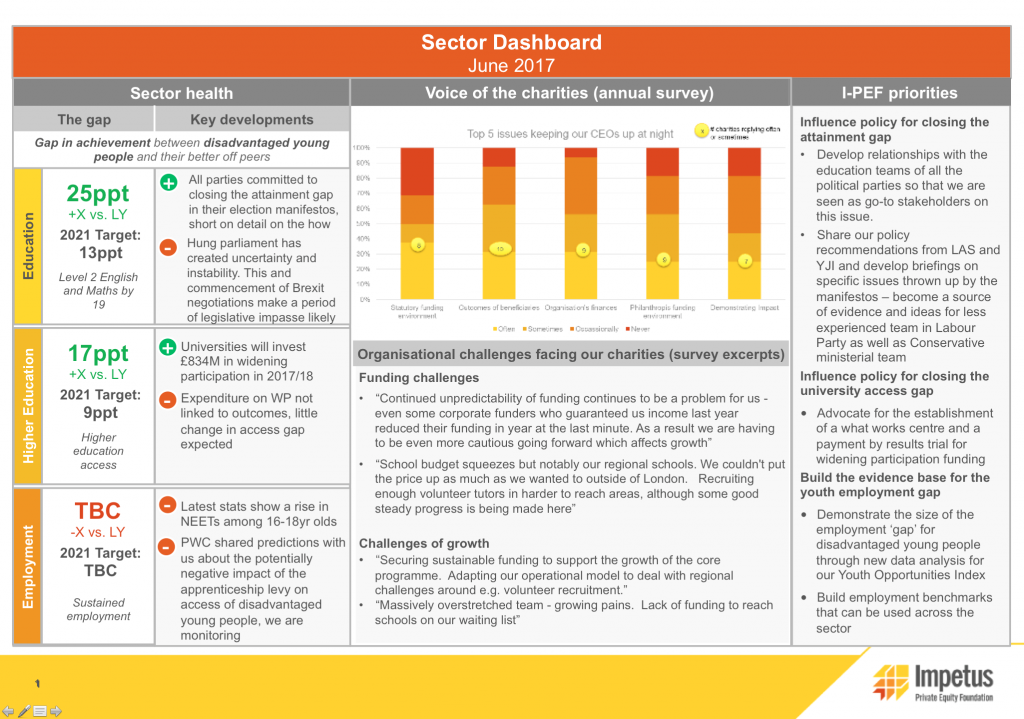

The first dashboard (shown above in draft form) will give Impetus-PEF’s leaders a high-level view of the education and employment sectors, key barriers to change, and Impetus-PEF’s advocacy priorities for addressing these barriers.

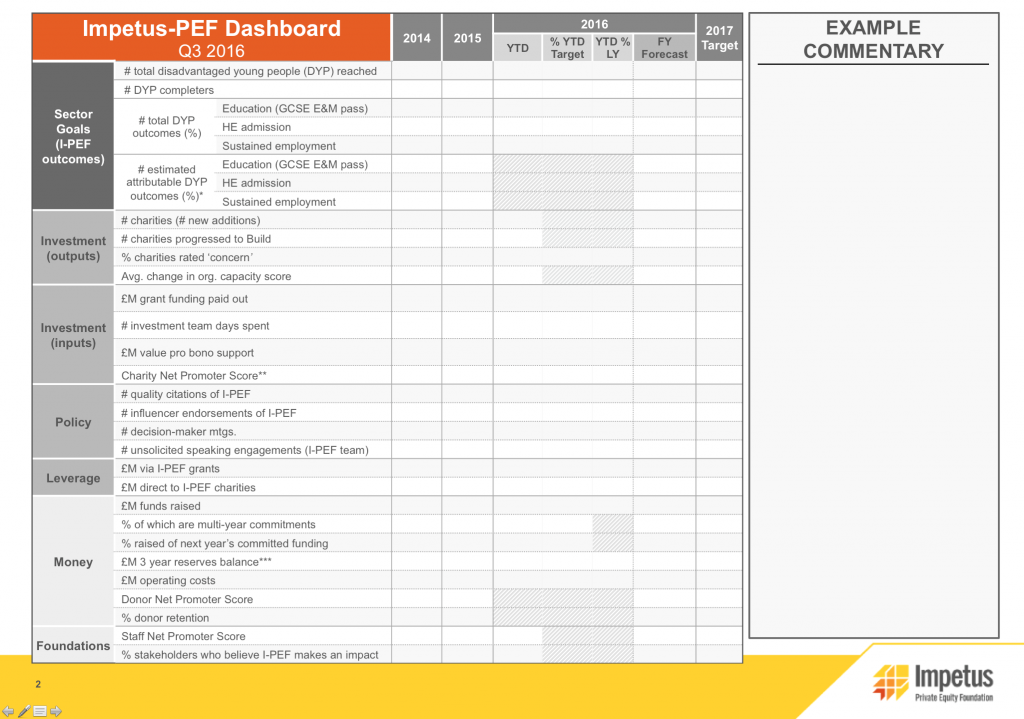

The second dashboard will give the executives and board an effective way to track contributions (outputs and inputs) to progress against the sector-wide goals.

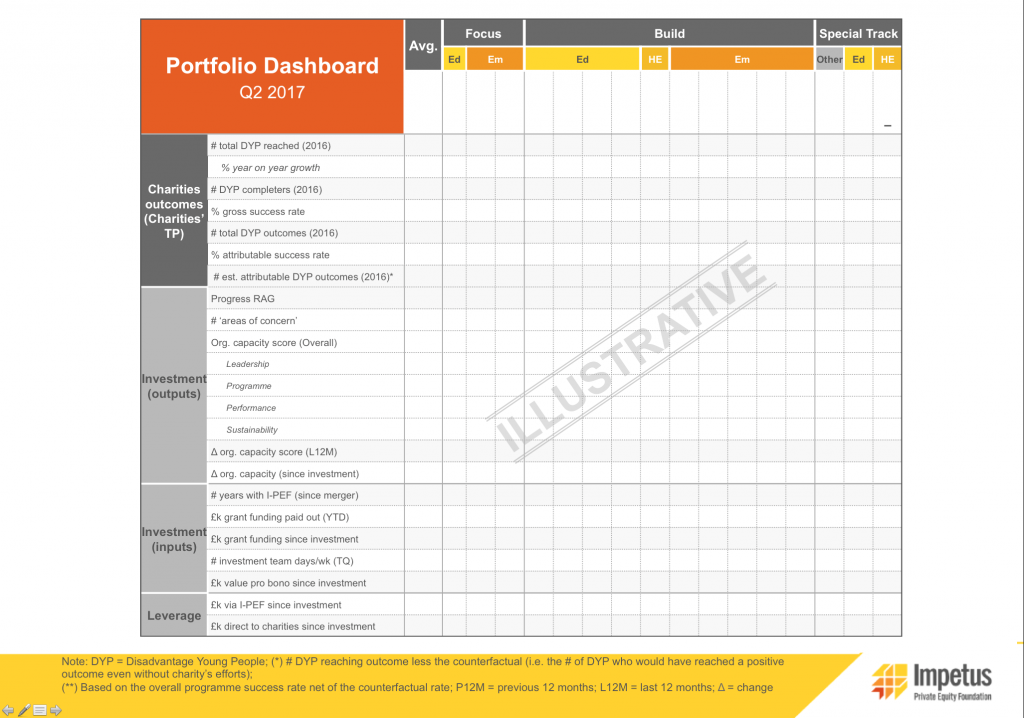

The third dashboard will help the executives and board track the progress of individual grantees in meeting the sector-wide goals (all data are illustrative).

Taking a sector-wide view “has been a really powerful conversation for us,” says Ratcliffe. “It’s helped us focus enough on … the cumulative effect of [our] investments and how we can make the biggest possible difference.”

Taking a sector view has also driven Impetus-PEF to invest in research and advocacy, not just in strengthening individual organizations. “Part of making a contribution to solving these big problems is convincing others to act, and in what ways,” says North. “We are interested in mining data to show where problems affecting our young people are being overlooked or where public spending isn’t making any difference. We can also show how our charities are trying new ways to solve problems that may have looked impossible, as well as making recommendations for systemic change. Then we look for others who may want to bring about, or support that change, so we can pool resources and get there quicker.”

Currently Impetus-PEF is looking at the area of post-16 education, where many disadvantaged young people end up in the UK. The organization is calling out poor outcomes and showing how better outcomes could be achieved.

Conclusion

It’s only been four years since Impetus-PEF began its performance pivot. Many aspects of their efforts, including the performance-management system, remain works in progress. But its leadership, management, and staff clearly have built an enduring commitment to, in words it shares on its website, “learning from and improving our own performance.” It’s relatively easy to challenge your grantees to improve their performance. It’s much harder to be introspective about your own.

Helping organizations advance significantly in their journey toward high performance takes patience and persistence, years not months. Early indications are that Impetus-PEF is on the right track. “Across the portfolio, we can show that the capacity of the organizations–in terms of leadership, systems, and financial viability–is getting stronger from working with us,” says Ratcliffe.

But it will take much more time and rigorous external evaluations to know whether the foundation and its grantees are having macro-level impact on the UK’s education and employment challenges.

Along the way, there will be white-knuckle moments. When grantees focus more of their resources on those who truly need their services and measure their outcomes in more rigorous ways, things can get ugly in the short term. Outcomes can actually go down and costs often go up. Grantees and the foundations that support them can lose their nerve.

We’d be shocked if Impetus-PEF does. It has the courageous executive and board leadership to see this experiment through–and share its successes and failures along the way.

Do you want to learn more about how donors and grantees can work together to enhance their effectiveness? Read about Funding Performance here, and let us know your thoughts.

Rice shares a story that illustrates the reciprocity of the learning relationship between Resurgo and Impetus-PEF. Impetus-PEF’s CFO Richard Lackmann decided of his own accord to take Resurgo’s five-day corporate leadership training. He was impressed by the training, especially the way Resurgo teaches and promotes “

Rice shares a story that illustrates the reciprocity of the learning relationship between Resurgo and Impetus-PEF. Impetus-PEF’s CFO Richard Lackmann decided of his own accord to take Resurgo’s five-day corporate leadership training. He was impressed by the training, especially the way Resurgo teaches and promotes “