Sign up for our monthly Leap Update newsletter and announcements from the Leap Ambassadors Community:

By clicking "Stay Connected" you agree to the Privacy Policy

By clicking "Stay Connected" you agree to the Privacy Policy

Feedback is an important mechanism for nonprofits to learn from their clients and make sure their services are meaningful and relevant. However, if institutions don’t consider specific populations, especially those marginalized by structural racism and other forms of inequity, in their questions, data collection, methods, and interpretation, feedback can do more harm than good. Vu Le, founder of Nonprofit AF, says, “When poorly thought out and executed, data can be used as a weapon to screw over many communities.” And in Weaponized data: How the obsession with data has been hurting marginalized communities, he writes: “Usually this is unintentional, but I’ve seen way too many instances of good intentions gone horribly awry where data is concerned.” That can happen, for example, when nonprofits gather feedback but don’t consider the best format for specific populations. Factors, such as language, familiarity with specific technologies, and level of trust, can influence who responds to a survey, which is why it’s important to involve clients in creating the feedback process and making sure it’s accessible.

Fund for Shared Insight, a national funder collaborative, seeks to improve philanthropy by promoting and supporting ways for foundations and nonprofits to listen and respond to the people and communities most harmed by the systems and structures they are seeking to change with their work. The collaborative believes that high-quality listening and feedback must be in service of equity. And that those who are most impacted but often least consulted by philanthropy and nonprofits can offer unique and valuable insight into how to bring about meaningful change, improving lives in ways people define for themselves. Melinda Tuan, Managing Director of Fund for Shared Insight, offers these tips to funders and nonprofits:

Tuan encourages different feedback methods for different populations. Since 2016, Listen4Good, a signature initiative of Shared Insight, has worked with hundreds of nonprofits to build their capacity to implement high-quality feedback loops with the people they serve. Those experiences demonstrate that one size does not fit all, and using creative ways to obtain feedback gives organizations the best chance to find out what a wider range of people really think. Elderly clients, for example, are more likely to prefer responding to surveys administered by paper and pencil or being asked in person, while teens are more likely to respond to text messages. A good strategy to get the perspectives of people in line for services at a nonprofit may be to stand in line with them.

Keeping equity goals in mind when instituting feedback is an important value and can lead to important changes in practice. When Listen4Good surveyed its 2017 and 2018 cohorts, 45% reported seeing differences in responses among sub-groups in their population when they segmented data, and 68% made changes within one year to respond to those differences. Another 21% planned to make changes.

Using an equity lens is critical for all stages of feedback. Professional data analysts often focus on the majority of respondents who give similar feedback and tend to ignore the outliers. But interpreting data through an equity lens means paying attention to all responses and looking specifically at how (and why) the outliers are different. In one example Tuan shares, a Listen4Good-participating organization looked more closely at the minority of respondents who said they didn’t feel included and found that most identified as LGBTQ. The organization went on to learn that their language, services, and content were not inclusive nor were they meeting the needs of LGBTQ people.

Tuan says these and similar lessons demonstrate why nonprofits must disaggregate feedback data and pay attention to perspectives from the margins. Other keys to implementing high-quality feedback loops include engaging clients throughout the feedback process; prioritizing voices least heard; including clients in decisions about how to respond to feedback, and closing the loop by engaging clients around the data and potential changes made in response.

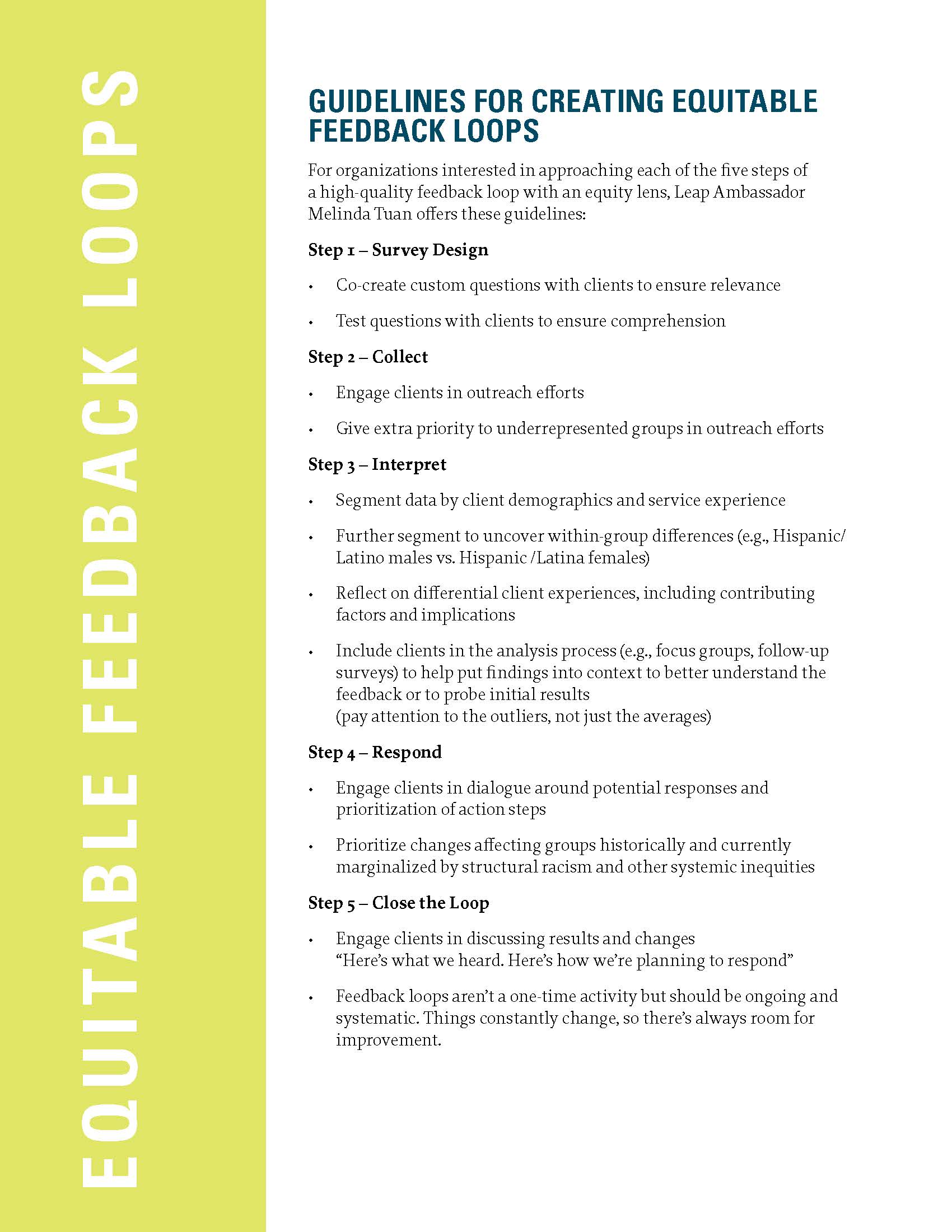

Guidelines for Creating Equitable Feedback Loops

Guidelines for Creating Equitable Feedback Loops

“Feedback opens the door to equity but doesn’t guarantee it unless participants are decision makers, and all of the voices are included,” says Mary Marx, President & CEO of Pace Center for Girls. Pace, which provides girls and young women an opportunity for a better future through education, counseling, training, and advocacy, collaborated with Shared Insight’s Listen4Good to implement equitable, high-quality feedback loops.

Marx says that feedback is now mission critical to their organization. The girls who participate in their program recognize and appreciate how they are listened to. As one girl says, “They make changes based on what we say.”

Pace began implementing several practices to engage girls, gain feedback, and make changes accordingly.

Feedback loops have changed Pace’s culture. The girls are involved in creating many of the questions in their feedback mechanisms, and relationships between team members and the girls have become more equitable. With the Listen4Good tool, the girls’ feedback helped identify staff behaviors that aligned with Pace culture and the organization then provided trainings to support the behaviors. For example, teachers received training on ways to support girls’ positive classroom behaviors and communicate clear expectations to strengthen their relationships with girls and a program support team was created to help support and sustain teachers’ new behaviors through coaching and ongoing feedback. In Centers with high social cohesion among team members, girls were more likely to improve academically and have longer length of stays. This was attributed to girls having a sense of belonging and feeling safe and respected. Pace trains and supports teachers in developing this type of culture in the classroom and among their colleagues to improve outcomes for girls.

The organization creates safe and trusting relationships by taking a collaborative approach and including the girls and their families in the design of their care. Often, the girls are a part of smaller decisions, such as changing their uniforms and food menus. Other times, they contribute to larger activities such as program design, as well as systems change projects. For example, a surprisingly high number of teenage girls were being arrested due to failure to appear in court. Through interviews conducted by the girls with judges, court personnel and the girls themselves, Pace learned that girls most often forgot their court date or had transportation issues. The adults suggested making a flyer, but the girls lobbied for a more practical solution—small cards to put in their cell phone pockets because they never go anywhere without their phones. The cards included court information, the court date, hotline number, transit information, and how to contact the court. Pace also created a video about what to expect if arrested. One year later, failure to appear in court had dropped 27%, a positive outcome that appears to be a direct result of using feedback and including girls in designing necessary changes.

Pace believes that one of the best ways to know if a program is effective is to ask those receiving services. Understanding their experience and what they find helpful, unsupportive, or impractical can open the eyes of team members to a pathway that works far better than the one in place. Another way is to ask those who aren’t receiving services. The Girls Coordinating Councils also include girls who aren’t part of the Pace program, so they too have a voice at the table. Pace undertook an RCT, published in 2018, that had extensive surveys of girls who didn’t attend Pace but were eligible to do so. Collecting this type of data may reveal barriers for those who aren’t being served by an organization and help a program eliminate obstacles.

Marx believes the focus on feedback, collaboration, and data disaggregation has led to a more effective program model. Pace tracked results in areas where the organization had responded to the feedback it received and found better teacher/student relationships, improved academics, greater self-efficacy, and a higher sense of empowerment. They also saw a higher retention rate, increased engagement, increased attendance, and a positive brand reputation, which is important since the program is voluntary. Being considered national experts is well and good, but nothing beats having a model that the girls believe in and that helps them succeed.

There are still nonprofits, funders, and other institutions that are not fully tapping their constituents to learn more from them and improve their program. Creating a feedback loop is critical, although not always easy. It’s clear that organizations need to be creative and involve their program participants when designing a feedback mechanism to better understand what works for specific populations. Who knows better what is working than those receiving services? So, let’s listen—and then act.

This document, developed collaboratively by the Leap of Reason Ambassadors Community (LAC), is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. We encourage and grant permission for the distribution and reproduction of copies of this material in its entirety (with original attribution). Please refer to the Creative Commons link for license terms for unmodified use of LAC documents.

Because we recognize, however that certain situations call for modified uses (adaptations or derivatives), we offer permissions beyond the scope of this license (the “CC Plus Permissions”). The CC Plus Permissions are defined as follows:

You may adapt or make derivatives (e.g., remixes, excerpts, or translations) of this document, so long as they do not, in the reasonable discretion of the Leap of Reason Ambassadors Community, alter or misconstrue the document’s meaning or intent. The adapted or derivative work is to be licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, conveyed at no cost (or the cost of reproduction,) and used in a manner consistent with the purpose of the Leap of Reason Ambassadors Community, with the integrity and quality of the original material to be maintained, and its use to not adversely reflect on the reputation of the Leap of Reason Ambassadors Community.

Attribution is to be in the following formats:

“From ‘Advancing Equity Through Feedback’ developed collaboratively by the Leap of Reason Ambassadors Community, licensed under CC BY ND https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/. For more information or to view the original product, visit https://leapambassadors.org/ambassador-insights/advancing-equity-through-feedback/.”

The above is consistent with Creative Commons License restrictions that require “appropriate credit” be required and the “name of the creator and attribution parties, a copyright notice, a license notice, a disclaimer notice and a link to the original material” be included.

The Leap of Reason Ambassadors Community may revoke the additional permissions described above at any time. For questions about copyright issues or special requests for use beyond the scope of this license, please email us at info@leapambassadors.org.

We use cookies for a number of reasons, such as keeping our site reliable and secure, personalising content and providing social media features and to analyse how our site is used.

Accept & Continue